Bridging The Gap: How Portsmouth, Derby and Oxford Survived the Championship

Portsmouth, Derby and Oxford defied the Championship's brutal welcome — not by dominating, but by adapting. This is how low-margin, pragmatic football helped them to survive.

Philip Webster

The jump from League One to the Championship is often the most brutal in the English football pyramid — a war for survival, not just a step up in class.

While the Premier League gets the spotlight, the Championship is where the second real bottleneck lies. Since 2015/16, around one-third of promoted League One teams have gone straight back down — a far higher rate than in other EFL tiers.

The average points tally for newly promoted clubs is just 52.8, barely enough to avoid relegation in 24/25. Unless you arrive with a rare blend of budget, talent, and top-level management — like Ipswich Town’s 96-point blitz in 23/24 — even big clubs often find themselves clinging on.

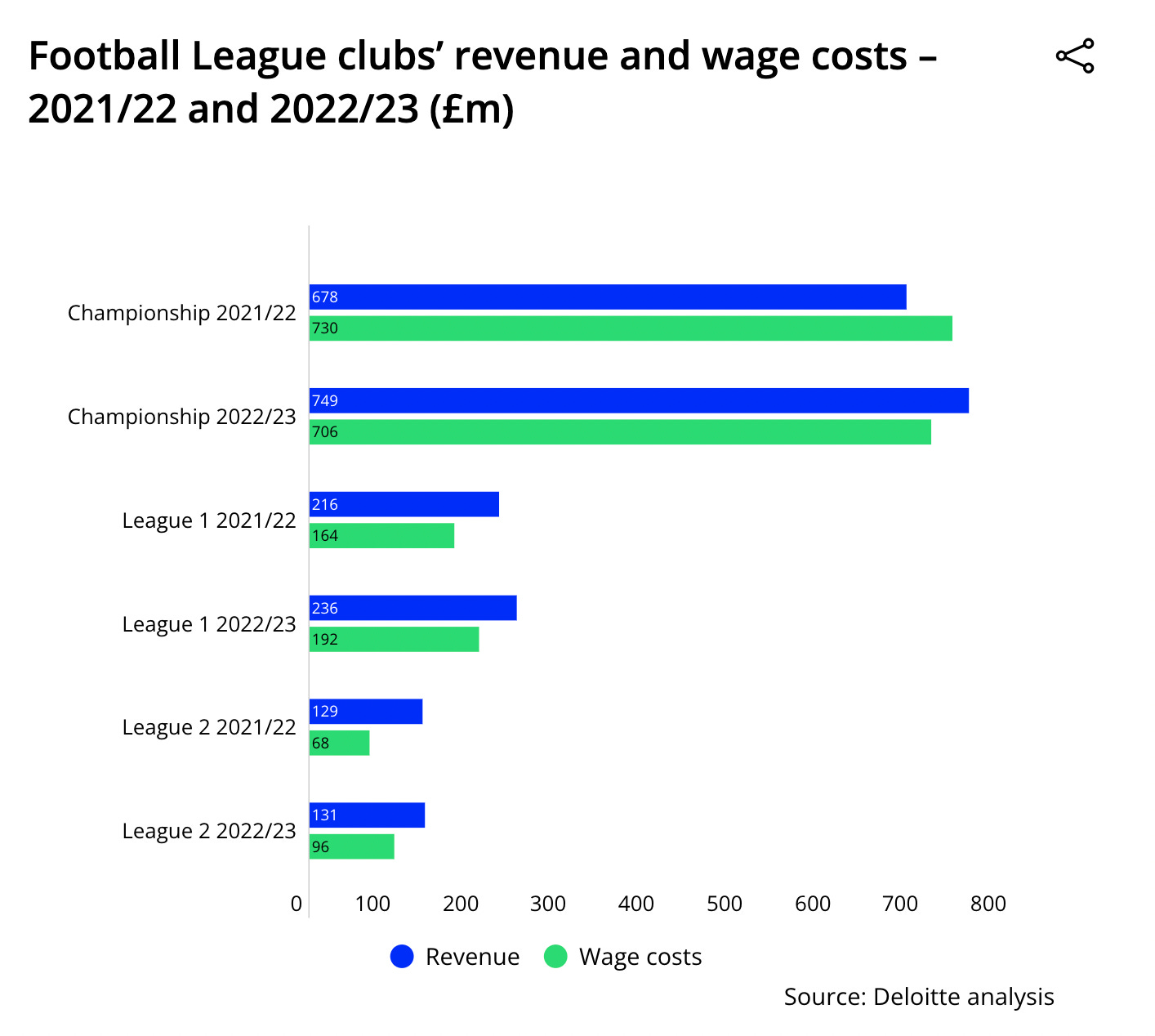

But why is it so difficult? Significantly bigger budgets mean the Championship has significantly more talented squads. This gulf is easier to digest by taking a look at Deloitte’s analysis below.

In the FA’s latest set of agent fees, Leeds spent £18,836,447 whilst Oxford spent £572,808. Championship revenue and wage costs overwhelmingly dwarf those of League One. Not only is it a massive gap, but teams are also having to catch up in an unprecedented manner.

And the eye-test confirms this when you watch these budgets play out on the pitch. There’s an obvious gap in quality between League One and the Championship, in a way you don’t see elsewhere in the EFL. It’s the ferocity of the game that makes the difference. The athleticism is almost incomparable – plus, athletes in League One can quickly look dreadfully outgunned in the Championship. A previously shifty, quick player will be made to look like they’re wading through treacle. And even the passing is more violent: the best teams in the Championship can forcefully snap passes through the thirds in a way you’ll never see in League One. The Championship introduces you to the end-point of football in the EFL: a raw blend of physicality and technical quality, played at a relentless tempo.

Oxford’s manager at the start of the season, Des Buckingham, pointed to this as the major revelation he saw when jumping levels.

“We’re probably covering anything between 100km as a collective to up to what has been 115km as our highest so far this season.

That’s probably 10 per cent higher from League One to the Championship. It’s not a significant jump in terms of distance, but the speed at which the game is played, our high-speed distance is 52 per cent higher compared to anything we had last year.

What it’s showing is that the total distances haven’t significantly changed, but the speed of the game is certainly significantly different.”

This article looks at how Portsmouth, Derby, and Oxford defied that trend, not with style, but with substance. Each team survived the Championship by embracing direct, low-margin football. Here's how they did it, and what it might mean for the clubs to follow.

Portsmouth

Portsmouth and John Mousinho’s journey from League One to the Championship is one of the most compelling, particularly because, unlike Oxford and Derby, they adapted together.

In League One, Portsmouth played a style typical of a top-six Championship side: controlling possession, building from the back, avoiding chaos. They ranked third for possession, fifth for pass accuracy, and 21st for inaccurate long balls. Precision ruled.

But in the Championship, that changed dramatically. They finished 19th for possession with just 44.6%. Beyond simply facing better opposition, Portsmouth actively shifted toward a more direct, pragmatic style. Their ten-pass sequences dropped from 410 to 197, and their passes per sequence fell from 3.16 to 2.46. They chose chaos over control.

This didn’t happen overnight. In their first 12 games, Pompey played expansively, with matches averaging three goals. After that point, games tightened to 2.7 goals on average. The early version of Portsmouth looked like a slight evolution of their League One selves. Afterward, Mousinho adapted, embracing guerrilla warfare on the margins.

Mousinho even reflected on this journey at the end of the season:

“At the start of the season, we were probably too focused on trying to build from the back and it cost us.

We had absolutely no qualms last season about going from back to front really quickly and, to be honest, we did that quite a lot in League One.

But one of the big differences in League One is when you are winning the league and going to sides, a lot of the time they sit off you and they let you play.

The worst thing you can do is to go more direct because they are sitting there ready to pick up the second balls and break from there. So you have to play.”

His humility in shifting away from a more fashionable style is what ultimately saved Portsmouth. It also reveals the level-headed manager they have.

The difference between the two versions of Portsmouth was stark. I saw them face Oxford twice at the Kassam Stadium — once as a top-of-the-table League One side, and then again as Championship survival candidates. The first was an end-to-end 2-2 thriller full of attacking swagger. A year later, the same fixture was a scrappy 2-0 Portsmouth win — low risk, low margin, and vastly more cautious, despite both teams fielding stronger squads. The contrast highlighted how context, not just quality, often dictates style.

That’s not to discredit the teams. Portsmouth’s survival was impressive, and Mousinho’s tactical agility even more so. Even within a more conservative setup, they maximised their attacking threats. Josh Murphy earned a shout for Team of the Year with 21 goal contributions, while Colby Bishop and Callum Lang combined for 21 goals.

Low-margin football gave Portsmouth a platform in the Championship. A gradual evolution back toward a more dominant style may follow, but for now, they’ve shown that adapting to the division is as much about pragmatism as it is about philosophy.

Derby County

My first-hand look at Derby County in League One came in a thrilling away game at Oxford. Oxford raced into a 2-0 lead, but Derby took over from there, dominating play, scoring three unanswered goals, and delivering the kind of comeback that sticks in the memory.

What stood out wasn’t a defined structure but the freedom Derby’s talented players had to express themselves. Kane Wilson, Eiran Cashin, Max Bird and Nathaniel Mendez-Laing were unplayable. It felt like they simply overpowered Oxford.

That same loose structure defined Derby under Paul Warne. At Rotherham, Warne’s teams played a thrilling, high-energy 3-1-4-2. But Derby never truly replicated that. In their promotion season, they ranked 19th in League One for high turnovers and 18th for shot-ending turnovers — the pressing intensity just wasn’t there. Nor were they dominant on the ball, ranking only 13th for possession. Derby relied on talent to overpower weaker teams but struggled against the top six: just 1.4 points per game compared to Portsmouth’s 2.2. You out-talent teams… until you can’t.

This isn’t to discredit Derby. Many talented squads have failed to get out of League One. Creating an environment where individuals can thrive is a managerial skill in itself. But that approach is vulnerable in the more demanding Championship.

Initially, Derby started well. A 4-0 hammering of Portsmouth in December suggested they had cracked the code. After 21 games, they were 14th, seven points clear of relegation. But without a clear identity, cracks began to show. Derby lost eight of their next nine, using a different formation in five of those games. That tactical drift cost Warne his job. By March 1st, Derby were bottom, four points adrift.

The turnaround began under John Eustace. Like Portsmouth, Derby shifted to a more direct, low-margin style — but crucially, they settled on a consistent structure. Across the final 11 games, Eustace stuck with a back-three that underpinned a rock-solid defence. Derby conceded more than 1 xG in just two of those 11 matches, including a 1-0 win at Hull that effectively sealed survival.

Tight, cagey football helped them stop conceding, but they still needed goals. Derby found their edge at set-pieces. If you lack the tools to open teams up in open play, you can dominate from dead balls. Derby scored a league-high 22 goals from set-pieces, a key weapon in a survival push built on small margins.

Just like Portsmouth, Derby pivoted to a direct, disciplined style that contrasted with how they earned promotion. That identity shift didn’t just steady the ship — it saved their season. Eustace deserves credit for instilling clarity and control when chaos threatened to drag them down.

Oxford United

Oxford had no business finishing above Derby and just one point behind Portsmouth. They ended their League One campaign 20 points behind both teams — and then lost Josh Murphy and his 21 Championship goal involvements to Portsmouth. For a 75-point side, even survival in the Championship should’ve been a long shot.

But a strong start gave them a vital buffer. After 11 games, Oxford were 10th — defying their pre-season relegation odds. Why? Unlike Portsmouth and Derby, Oxford already played a style suited to the Championship. While Derby leaned on talent and Portsmouth on possession, Oxford were built around pace, counter-attacks and punishing turnovers.

They ranked just 12th for possession in League One, but first for shot-ending turnovers — five more than the next best. They didn’t dominate the ball; they were drilled to strike without it.

Their playoff run reinforced this strength. Against high-quality Peterborough and Bolton sides, Oxford conceded just once across the two legs. Their 4-3-3 “reverse mullet” formation — punchy in attack, secure in defence — thrived in reactive, tight matches.

But like the others, Oxford hit a wall. After reaching 10th, they lost seven of nine games, five of them by two or more goals — not just unlucky, but overwhelmed. Injuries played a role, but teams had figured them out. Opponents contained their early passing patterns, forcing aimless possession or desperate long balls — huge risk for little return.

That run cost Des Buckingham his job. In came Gary Rowett — the EFL’s blueprint for low-margin pragmatism. He quickly installed a 4-2-3-1 focused on vertical passes and field position. After losing five games by 2+ goals in a nine-game run, Oxford would lose by that margin just three more times all season.

This shift was reinforced by a bold transfer: signing 29-year-old centre-back Michal Helik. Known for aerial dominance, Helik marked a break from Oxford’s tradition of developing younger, technical defenders. He anchored a backline that kept 13 clean sheets — 12th-best in the league — and became a key weapon in attack. His five goals in 20 games added a new edge.

Against Sunderland in Oxford’s final home game, they couldn’t match their opponents in flair, but Helik’s physicality was unplayable. He scored the crucial second goal, a clear example of how Rowett’s pragmatism leveraged set-piece mismatches to steal points.

Oxford also became the EFL’s top team for goals from long throws, and second in the league for set-piece goals behind Derby. For a side that posted the second-lowest xG total in the Championship, these were vital margins.

By the end of the season, Oxford joined Derby and Portsmouth in the bottom five for possession — three clubs once known for flair, now united by tenacious, direct, survival-first football.

Promoted teams: find your point of difference

Do this season’s survival stories mean anything broader for the EFL? Maybe. It could be that Portsmouth, Derby, and Oxford simply found timely solutions, but together, they suggest there's value in challenging the Championship’s prevailing tactical trends.

Trying to mimic the league’s top teams — or worse, a diluted version of Premier League styles — rarely works. As we’ve seen in the top flight, smaller clubs that try to echo the “big six” often end up as pale imitations. But by disrupting those styles with directness, physicality, and tactical discipline, you create mismatches that can yield real rewards.

Looking ahead, this model may not apply to Birmingham and Wrexham, who are backed by budgets that will rival the top half of the Championship. But Charlton, under Nathan Jones, could follow a similar survival formula: defensively resilient, happy without the ball, and equipped with unorthodox threats.

Even the clubs promoted to the Premier League might draw lessons. Leeds, Sunderland, and Burnley could ask themselves whether fighting fire with fire is wise, or whether a shift toward a compact, counter-focused style might offer a better path. Sunderland’s 4-4-2 could prove sneakily effective, while Leeds’ rumoured re-evaluation under Farke shows they’re at least asking the right questions.

But the main takeaway is for fans of Portsmouth, Derby, and Oxford. Each club delivered an exhilarating League One promotion — then got smacked by the Championship’s intensity — before regrouping to survive with grit, adaptability, and no illusions. They succeeded not by playing prettier football, but by playing smarter, tighter football. In a division where fine margins matter most, their willingness to embrace a different style made all the difference.

One of the best articles I’ve read on the platform. Perfect balance of insight and story telling. Will be interesting to see how Charlton go about it this season!

Brilliant read this.