Can Manchester United’s “Dead President” logic help unpick the managerial perception gap?

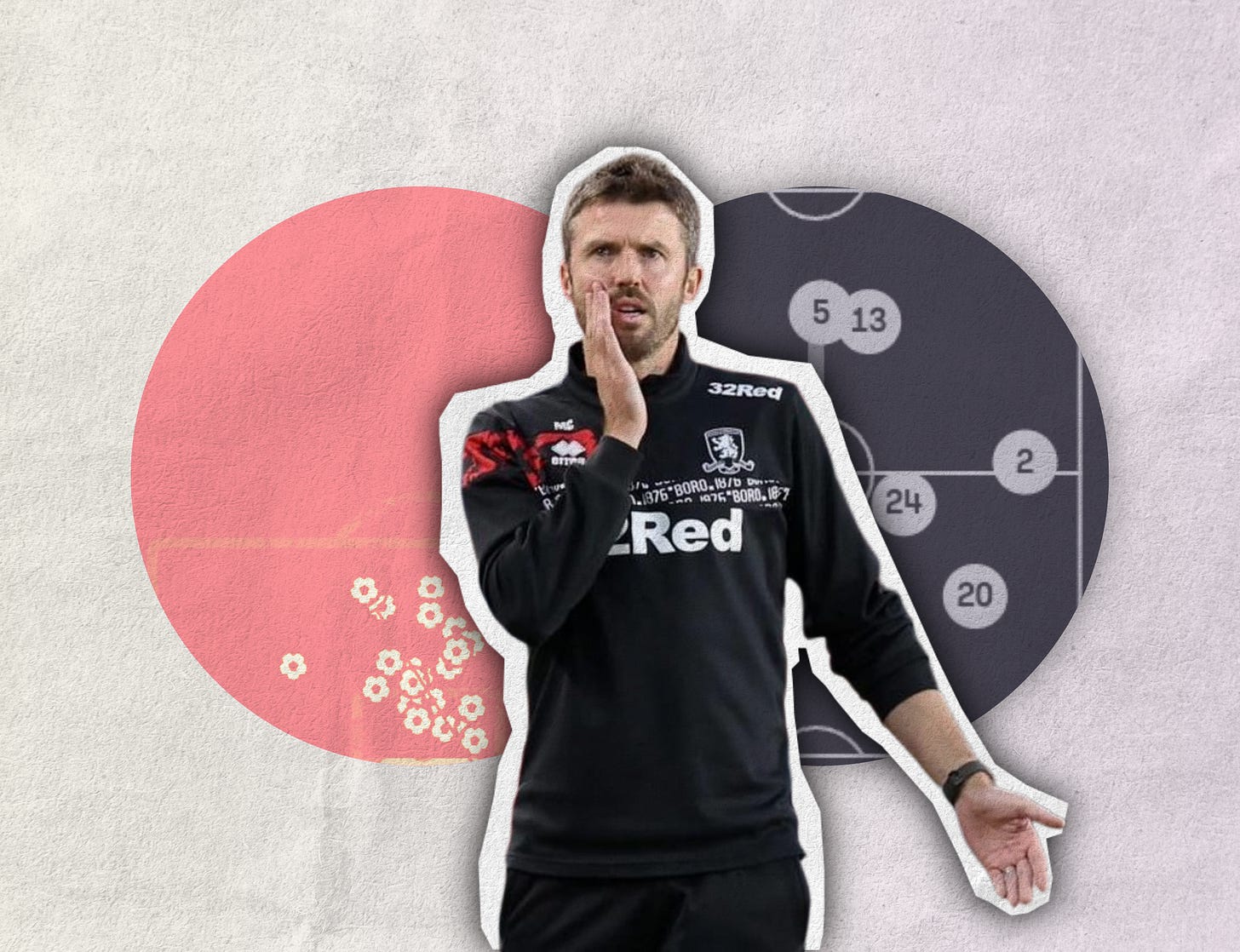

Michael Carrick’s appointment may help challenge long-held assumptions about EFL managers, even as Manchester United follow their well-trodden path.

Words by Sam Parry

“One out of every four Presidents has died in office. I’m a gamblin’ man, darlin’, and this is the only chance I got.”

That is how Lyndon B Johnson explained his decision to accept the vice-presidential nomination with John F Kennedy, when it was a job he openly despised. The logic held. Johnson became the 36th President of the United States.

Your best odds of managing Manchester United? Be a well-regarded partisan and wait for the president to die.

They gave it Giggsy.

They gave it Ole.

They gave it Carrick.

They gave it Ruud.

They gave it Fletcher.

They have only gone and given it Carrick again.

It is no longer the Glazers but Jim Ratcliffe’s INEOS group turning the pages on this Choose Your Own Mad Venture. Far from straying down divergent paths, Manchester United are following the route well trodden.

The logic of picking from a narrow selection of ex-players is self-evidently limiting. But is strict adherence to that formula now providing, almost accidentally, an evidence base that “give it to a talented EFL manager ’til the end of the season” shouldn’t be considered any less mad?

The latest president to fall is Ruben Amorim. He brought with him an unambiguous commitment to a 3-4-3 system that would, somehow, eventually click into place. There has been fair criticism of his lack of adaptability. But the idea that the manager of the top Portuguese team is inherently preferable to the manager of the top Championship team, when (per Opta) the Championship is rated as the stronger league, amounts to a judgement. The question is what, exactly, is being judged.

Which brings us to Michael Carrick. Like all new managerial appointments, his record is being pored over, from win percentage and xG to tactics and PPG.

The naysayers will overemphasise his sacking by a Championship club, with short shrift given for Middlesbrough’s dominance on the ball or the sometimes bewildering gap between their goal return and underlying numbers. The optimists, meanwhile, will lean heavily on those same underlying metrics, with less consideration for their decline over the course of his tenure.

Still, by most measures, he is easy to dismiss: a former Middlesbrough manager who, with all due respect, is stepping into a job operating at an entirely different altitude and budget. At that altitude, with that budget, comparisons between the two roles should rightfully be treated as close to meaningless.

Judging Carrick purely on his spell at Boro also misses another, broader and more uncomfortable point. The Championship has quietly become a preparatory school that flunks almost every graduate. Championship managers – including those who take their clubs into the top flight – are judged for being somewhat… ‘Championship’.

Over the past decade, a succession of managers have won promotion, over-performed, built something genuinely impressive, and then found that experience repurposed as evidence that they never truly belonged.

Kieran McKenna was overlooked during the Manchester United recruitment process that ended with Amorim, and back in 2019, Chris Wilder was briefly linked with the Arsenal job. But, from Steve Cooper and Scott Parker to Daniel Farke and even Marcelo Bielsa, Championship success stories rarely get their chance to manage at the top of the English pyramid.

The positivity of promotion so quickly becomes a charge sheet when relegation arrives, despite it being highly likely if not always inevitable. And yet one of their contemporaries, without a promotion to his name, has just landed the Manchester United job not because of his managerial CV but because of his playing one.

So pause for a moment. Which path to hiring, even as a stop-gap, makes more sense? Limiting yourself to a pool of ex-players, or recruiting from a pool of serial success stories? The answer doesn’t really matter – because the answer, this time, is Carrick.

Why, then, is the EFL pipeline so often ignored? One explanation is the flawed idea of experience. These managers lack experience in the top flight, experience at a ‘top club’, or experience as Pep Guardiola’s assistant at Manchester City (see Mikel Arteta and Enzo Maresca). But experience itself is not the real barrier. Reputation is.

Guardiola himself once pointed to the limits of managerial context. “If he [Chris Wilder] was here, he would be fighting for the title. If I was in Sheffield, I would be fighting relegation.” The point isn’t that Carrick could be Pep reborn, nor that Pep would fail at Bramall Lane. It’s that a teeming array of factors, from win percentage to communication style, appearance to tactical preference, overwhelms a manager’s reputation. That reputation then becomes overvalued in the hiring process.

Nothing puts a blot on a manager’s reputation like relegation from the top flight. But those who stay up, and even thrive, are tarnished by the impossibility of playing a certain brand of football. It is plainly the case that Chris Wilder could not have implemented a Guardiola-style system with the players at his disposal in the Premier League. Put another way: it takes elite players for a manager to succeed with elite ideas, and EFL graduates rarely, if ever, get the chance to prove they belong in that space.

Carrick, sacked by Middlesbrough, does get that chance. The lack of a Premier League relegation on his CV may, somewhat perversely, count in his favour – although Vincent Kompany, with a relegation on his CV, moved directly from Burnley to Bayern Munich. Clearly, there is some level of cognitive dissonance affecting the thinking among elite English clubs.

Perhaps Carrick (or Liam Rosenior) can help to demonstrate that a spell at Middlesbrough (or Hull) tells us remarkably little about whether someone can manage Manchester United (or Chelsea). Perhaps, if they are seen to succeed, it will be easier to accept that hiring managers from so-called ‘lesser’ clubs is not charity, nor recklessness, but potentially just basic competence.

Which brings us back to LBJ. Waiting for the president to die, and recruiting from a talent pool as narrow as that club’s popular former players, is not competence. But it just so happens that the logic has spat out an individual who is untested at the level except for a caretaker spell of three matches (W2 D1), and whose managerial CV consists of a single EFL club and no silverware. The latent narratives that could grow from this petri dish have piqued an interest in a top-flight team that have no business being in this newsletter.

But people of a certain age still retain a flicker of curiosity whenever a new Red Devil-shaped air freshener is installed at Old Trafford. Like Shredder, Dr Octopus or Magneto, Manchester United were the cartoon antagonists of my footballing childhood. Too big. Too good. Unstoppable. The old joke about never being more than five metres away from rats and United fans once felt universal. I doubt the TikTok generation have ever heard it.

To them, and to others, Carrick may be seen to succeed or he may be seen to fail. Either verdict will have little to do with his background as an ex-player or an ex-EFL manager. More likely than not, one outcome will be held up as proof, the other as a warning.

Less likely, but more hopefully, I find myself oddly lashed to the mast of Carrick’s interim spell. For those of us who would like to see a clearer pathway for EFL managers, there is something to be gained here. Can the individual tasked with turning the ship around prove the perception gap is far greater than the talent gap?

Good read. I want to see Carrick succeed for similar reasons.

Oddly enough, the closest thing to him is probably Gareth Southgate. A man who couldn’t possibly be any good because he’d “failed” and eventually been sacked as a young manager at Boro.

But he had the talent and personality to do something almost no-one has done in the modern era, get England playing good football and competing at the very top table.

Excellent well written and argued article. A short summary is 'the way football manager appointments are decided is bonkers, particularly at Man Utd'.