CONTROL: The danger in having it all

Burnley’s risk-averse style is creating less joy, more division, but is it self-defeating as well as dull? And could Birmingham end up going the same way?

Huw Davies

One word. English football goes through phases in which one word suddenly invades every coach’s lexicon and press conferences. ‘Transitions’, for example, replaced ‘counter-attacks’ in footballspeak almost overnight. ‘Conditioning’. ‘Thirds’. ‘Intensity’ was a big one, starting around the time that Jurgen Klopp arrived from Germany – suddenly every manager was talking of wanting intensity from their attackers, their midfielders, their fans and their tea ladies.

‘Control’ seems to be the new watchword. It's especially popular among promotion/title favourites whose young, ambitious managers want to play games on their terms, reducing opponents to NPCs. Birmingham City’s Chris Davies, for example, told Sky Sports’ Adam Bate in 2023:

“Controlling the ball to control the game is still, overall, the better way to get results. There are other ways, and for different sets of players, but for me it is still the best way. Ultimately, it’s about believing it is effective. I worry when I hear people talking about [prioritising] its aesthetic appeal; you have to believe it is an effective style of football.”

That’s why this differs from the debate over Russell Martin, Ange Postecoglou (Davies’ old boss) and other coaches who want their players to pass the ball short and play out from the back in any given circumstance. That philosophy deliberately invites danger. Davies – whose name really does make it sound like I’m writing in the third person, i.e. even more pretentiously than usual – is talking about controlling a game: that means keeping possession, but also regulating your own attacks just enough to pre-emptively prevent opponents from hurting you on the break. It’s pragmatism.

But it can be too pragmatic. For one thing, as we’ve seen with Burnley this season, it can become joyless. Reward requires at least some risk if it’s to be rewarding. That doesn’t mean you have to go Full Ange and risk everything all of the time, but giving up a part of yourself is key to fulfilment, and if that’s too pretentious (I did warn you), then the meat-and-potatoes problem is this: if a team tries to avoid ever putting itself at risk, it becomes stale and easy to stop.

This emphasis on control-at-all-costs applies best to Arsenal as well as Burnley – two clubs having ostensibly decent seasons, sat 2nd and 3rd in their respective divisions, but who may have blown their chance of, in turn, winning the Premier League and winning automatic promotion to it. Arsenal are of another parish, or gated community, so let’s give them the TL;DR treatment: having twice fallen just short of lifting the title, Mikel Arteta became increasingly focused on eliminating peril at the expense of penetration, prioritising defence over attack on the pitch and in the transfer window, which generally made his team more predictable and reliant on set pieces.

Scott Parker’s Burnley provide a perfect EFL example, as summarised by Daniel Farke after Leeds’ 0-0 draw at Turf Moor. Roll the tape:

“They have a special approach… They take pretty little risk with the ball, so if they lose the ball then it’s just in areas where they can’t be hurt on the counter-attack. This is why you never have a counter-attack or really dangerous transition against them. You have to prepare to create a chance always, more or less, against a compact block. Credit to Scott for how he does this.”

He’s not wrong: WhoScored tells us Burnley haven’t conceded even once to a counter-attack, which has helped them to concede only nine goals in total. Parker has, in a way, taken the concept of a counter-attack and turned it into counter-defence. Instead of thinking, out of possession, ‘How can we win the ball and attack?’, Burnley are in possession and thinking, ‘How can we avoid losing the ball and conceding?’

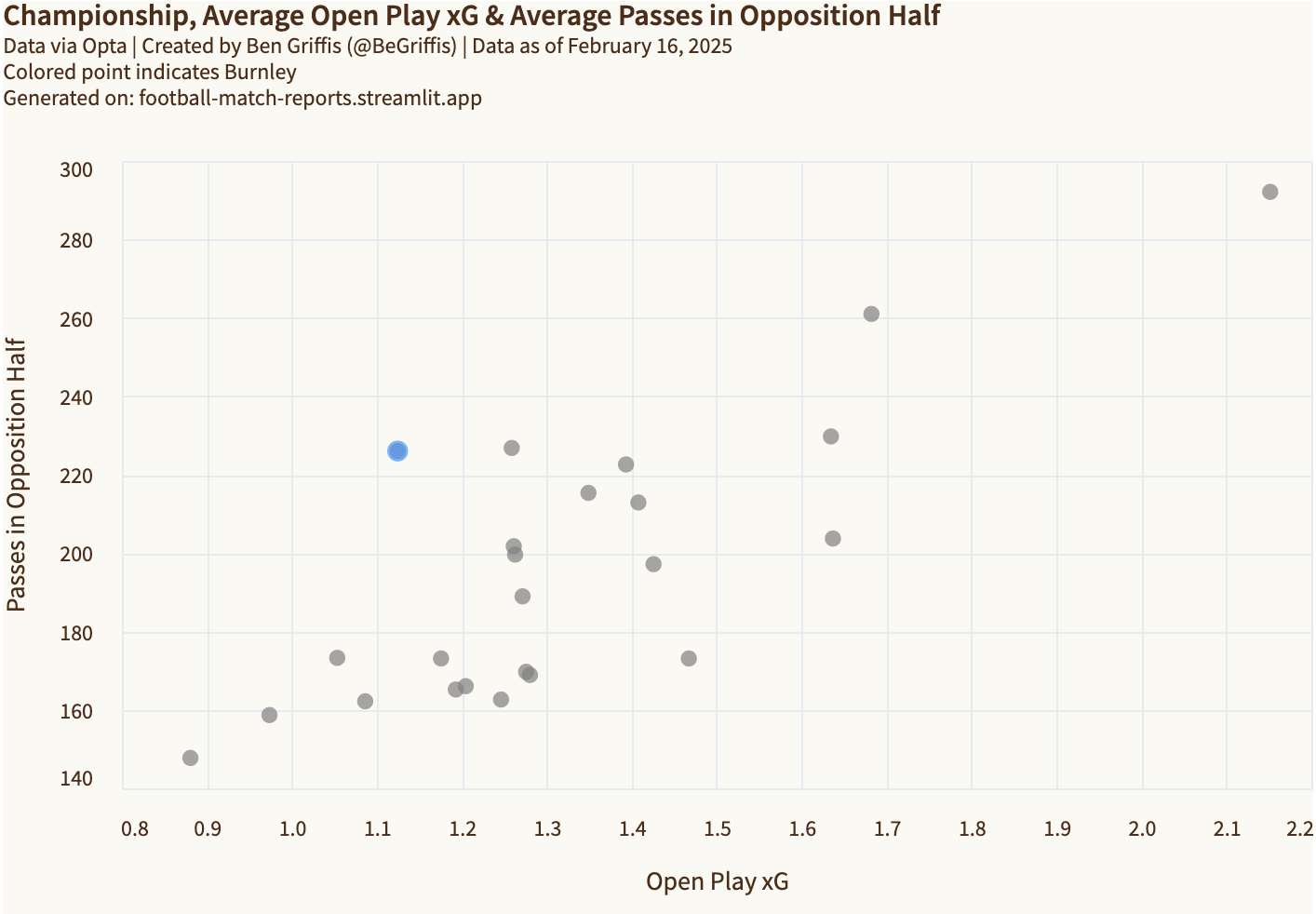

There is, however, a trade-off. Parker’s side have found the net themselves so rarely since August that more than third of their Championship goalscorers this season (6 of 17) aren’t actually at the club any more. They’ve shown a bit more attacking intent of late against bottom-half teams – though even then they won 1-0 and, brace yourselves, 2-0 before drawing 0-0 at Preston – but for all of their possession in hypothetically dangerous areas, their xG for the season still looks like this:

It’s especially, painfully evident at Turf Moor. Only Hull have scored fewer league goals at home than promotion-chasing Burnley. An aggregate score of 18-4 across 16 fixtures looks like a good case for the defence, because they’ve let in half as many goals as table-topping Leeds, but that just means that Leeds are conceding once in every two games rather than four… while scoring 44 goals to Burnley’s 18. The Clarets’ defence has passed the point of efficient usefulness. It’s like having an oversensitive new burglar alarm – hey, no burglars, but it goes haywire if we try to leave the house.

The result is a Burnley home record of W8 D8 L0, averaging 2 points per game: not exactly bad, but not exactly the 2.38ppg and 2.59ppg averaged by Sheffield United and Leeds, either. If you can’t win, don’t lose, but those dropped points already look costly. Farke described Burnley 0-0 Leeds as “a chess match”, using that analogy, Parker has seemingly decided it’s better to accept the stalemate than suffer the zugzwang.

One argument is that this approach prepares you for life after promotion, assuming it doesn’t stop you winning that promotion first. Does it? Premier League defences are certainly harder to breach than Championship ones, but I’d argue the step up in attacking quality is even greater, so you’re going to keep very few clean sheets whatever happens, and therefore being able to win games when you do keep zeroes and ones is vital. You can still win a match in which you concede – it’s hard, but you can. You can’t win when you don’t score as a result of an inadequate attacking plan.

The irony is that if Burnley do go up in this guise, staying record-breakingly strong defensively but without improving their attack, they’ll realise they can’t control games in the Premier League. The opposition threat is simply too great. They’re Jupe, trying to tame a far more powerful beast, beyond their reach and understanding. You might get away with a single Star Lasso Experience if you’re lucky, but soon enough you’ll be sucked up, chewed up and spat out.

Birmingham are far better prepared for what is a far smaller step up, but it will be interesting to see how Davies develops his approach when yes, when, not if – they’re promoted to the Championship this year. There’s every chance he won’t change anything. An emphasis on control should stand them in good stead because the jump in opposition attacking quality isn’t the same as the rocket-boosted trampoline into the Premier League; there are fewer game-breakers to break your game. Even so, stepping up may require a slight increase in ambition on the pitch to match the club’s sky-high ambition off it.

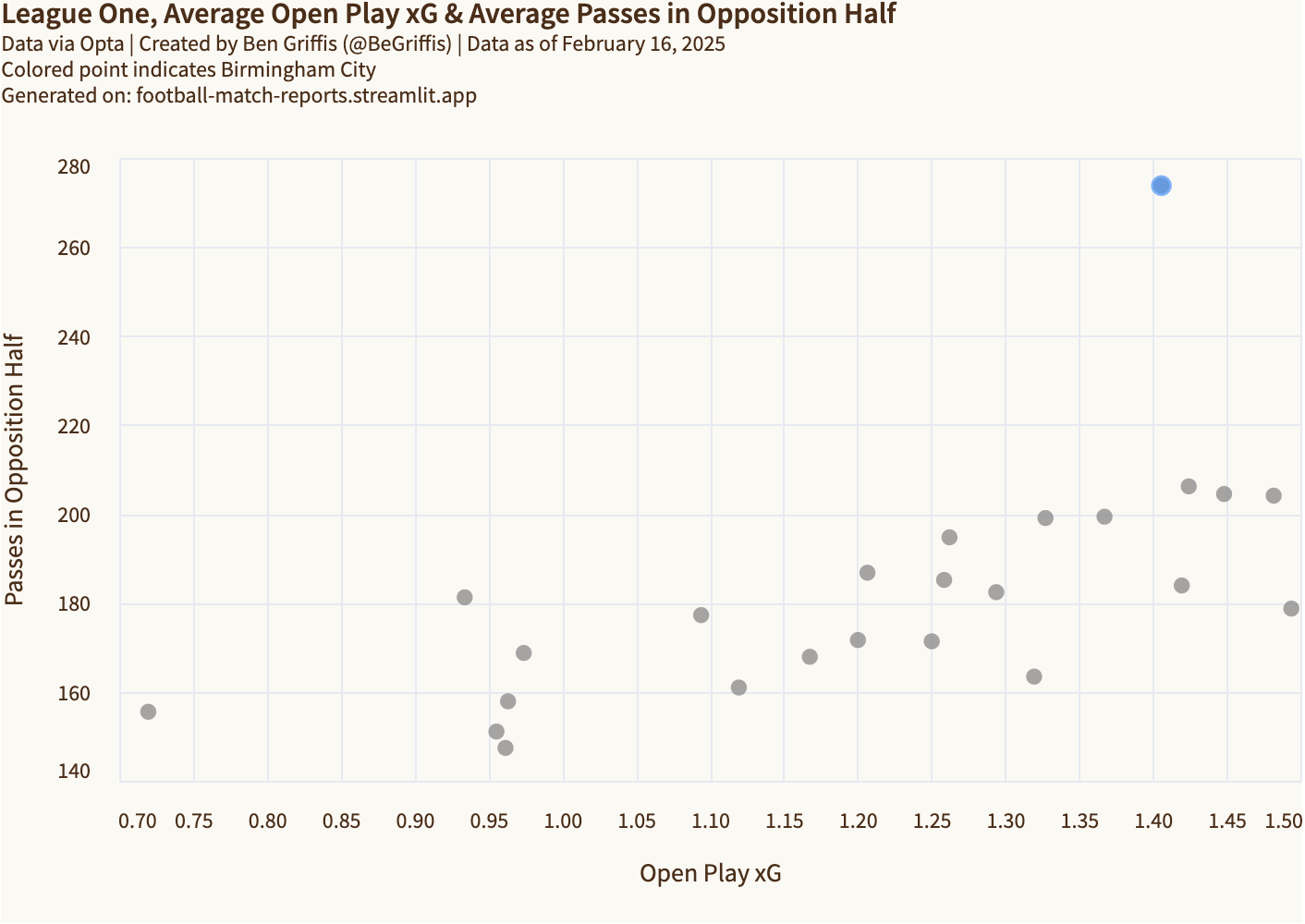

Statistically, Birmingham’s ball domination this season borders on comical. With 65.8% possession, they average 10% more than even the next-most possession-based team (Bolton, second on 55.6%). Davies’ side therefore have the opportunity to do more with the ball, because on average they have it in their control for nearly 10 minutes more ball-in-play time than any other League One team.

And yet. While these statistics do feed into themselves to an extent, it isn’t ideal for a team with this much possession to rank, per 90, down in 6th for xG in open play, 8th for shots taken inside the area and 15th for ratio of xG to xT (expected threat, which assigns higher value to all actions, including passes, that are made closer to the opposition goal).

It doesn’t define this team but in some games, there’s an extent to which Birmingham rely on Jay Stansfield, or sometimes Tomoki Iwata, to win the game by being better than League One defences while their team-mates facilitate a safe space for them to do that. That’ll work against Charlton, when Stansfield scores an entirely individual effort in the 23rd minute and Birmingham are content to share the remaining three-quarters of the game evenly for a 1-0 win (and I do mean evenly – the xG count after that was 0.35 v 0.35), but Charlton aren’t in the Championship. The Blues will need to do more next season, and even more than that if they fulfil their aim of achieving back-to-back promotions.

The league table is ordered by points before goal difference, but it is remarkable that a dominant, table-topping team such as Birmingham should have won 21 matches but only two of those by more than two goals. Some 21 other EFL clubs have covered the -2 handicap in more games this season, and none of them with the scale of Birmingham’s relative resource advantage. Cut loose, already! Didn’t that recent 4-0 annihilation of Cambridge feel good? Try it more often!

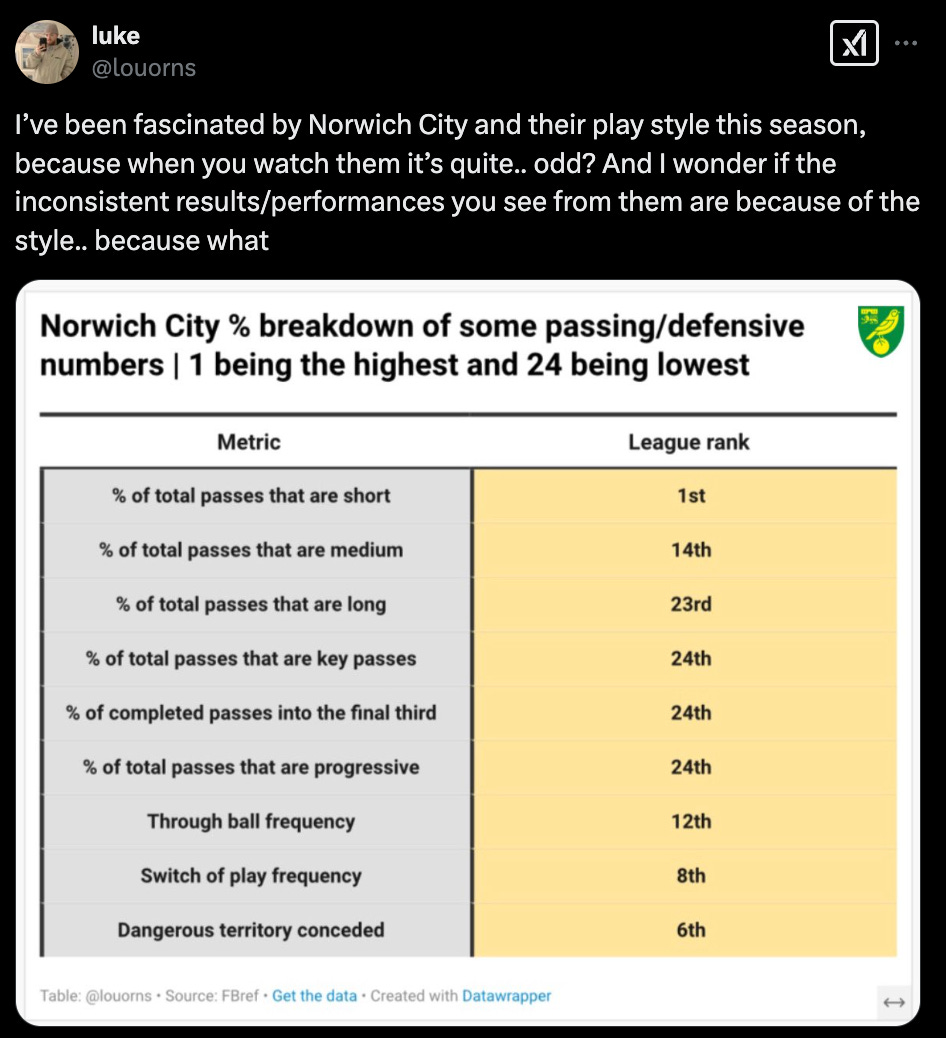

Still, a win is a win is a win is a win. Burnley aren’t getting enough of them, and there may be a similar situation unfolding at Norwich, who’ve engaged in safer and more passive possession than before.

That could perhaps have started as a reaction to losing star talents – Gabriel Sara to a summer sale, Josh Sargent to injury, Borja Sainz to a long suspension – but it has placed more pressure now on Sainz refinding his early-season magic and Sargent being more efficient with fewer opportunities. In their last three matches, oldest first, Norwich have had:

65% possession, 0.69 xG and 2 big chances against Derby (H), drawing 1-1;

59% possession, 0.72 xG and 0 big chances against Preston (H), trailing for 85 minutes and losing 1-0;

60% possession, 1.42 xG and 2 big chances against Hull (A), drawing 1-1.

That performance against Hull was an improvement but it took Norwich a while to get there: in the first half, they had as much as 66% possession but took only three shots. With his surname like the sound of a net rippling from a sweetly-struck shot, I call upon Johannes Hoff Thorup to unleash the kraken.

All of this isn’t just about the potential perils of passing football, because if Russell Martin’s Southampton defence taught us anything, it’s that ‘control’ isn’t synonymous with such a system. There is a discussion to be had about whether it works (in fact, we’ve had it here), especially considering that the third- and fourth-most possession-happy sides in League One, Crawley and Peterborough, currently occupy places in the bottom five. That’s a slightly different argument, though, because it applies to teams across the financial spectrum; Crawley are hardly failing, while Martin, Luke Williams, Ian Evatt and Mike Williamson share a playing philosophy as well as a recent P45 but they weren’t all managing HMS Piss The League. What links Arsenal, Burnley and Birmingham here is their resource advantage over most opponents, and the question of whether seeking control rather than carnage gets the most out of that.

This isn’t purely about risking defeat to turn a draw into a win, either. It’s a question of how you attack, and whether you can do that effectively, dangerously, while trying to retain ultimate control of all possibilities. Even Pep Guardiola, football’s great control freak, saw a reason to spend £100m on a socks-rolled-down maverick in Jack Grealish. The fact that Grealish has since been Stepfordised at Manchester City doesn’t change that.

Jonathan Wilson suggested recently that, “In football there does appear to be a movement away from the rigid control of a Guardiola”, which some might argue is, well, the exact opposite of what I’m saying. I’m not going to go up against the big dog, but I do also see something in what he writes soon afterwards about Louis van Gaal in the 1990s: “He played the familiar Dutch 4-3-3 but insisted that if his wingers had more than one defender between them and the space they were attacking, they should turn back inside rather than risk losing possession and being caught on the counter.” Personally, I feel as though we’re seeing this a lot right now.

And then, of course, there’s the question of joy. Here’s Clive Whittingham from the wonderful Loft For Words, after Burnley had faced QPR and recorded the third of their 11 goalless draws so far this season:

“It’s all just so, so slow. Backwards and forwards and sideways and sideways… Just as at Mitrovic-led Fulham, or Solanke-led Bournemouth, Parker is a guy in possession of a nuclear weapon, trying to win a war with a toothpick just to prove he can do it. For goodness’ sake, get on with it. Have some fun. It’s meant to be fun, this.”

I don’t agree that Parker’s doing it to show off, and Burnley fans would argue that they don’t have a nuclear option this season (just a well-stocked arsenal of assault weapons), but the effect is the same: every Clarets match becomes a low-margin affair.

One-third of Burnley’s league fixtures this season have ended 0-0. That is a staggering number. A few more staggering statistics for you: more than a third of the goals that they have scored came in just three fixtures; take away their first two matches of the campaign and they’ve scored less than a goal per game; and while their 11 consecutive clean sheets since Christmas is truly remarkable, a glitch in the system, their 10 games after Boxing Day have featured a total of one goal scored after half-time. Won’t somebody think of the children?

Control is a hell of a drug. Parker, Davies, Arteta and more must just be careful not to overdose on it.

Very very interesting article. As a blues fan, watching us pass the ball around slowly at home in front of a low block gets tedious quite quickly. I don't think we're as bad as Burnley, and Davies is quite pragmatic and happy to go long to beat a press or put the big men on for the last 15 mins and get the crosses in, but thrilling to watch we are not. St Andrews faithful get quite frustrated and frankly bored.

The XG picture is interesting, we do score goals and we do score low XG goals (see messrs Iwata and stansfield) but I think we're geared to create a small number of high XG chances not lots of low ones. We rarely take longshots outside of second phase deadball situations. This results in low XG.

In the championship I think you'll see more gegenpressing type goals as we face better opposition. It's a key part of davies philosophy that hasn't seen much use yet due to our domination of possession. And maybe our games will be more exciting, more like the Newcastle FA Cup tie.

On the other hand I could see a difficult second season for Davies if the football is boring and we're in midtable with little to play for this time next year. He's still a young coach though and clearly capable of adapting. Gonna be interesting!