English Football's pyramid scheme

Why preferring the EFL to the Premier League is to prefer the unpredictable to the predictable, the drama to the melodrama, the goal to the maybe-goal, and the competition to the procession.

“The thing about football — the important thing about football — is that it is not just about football.”

Terry Pratchett, Unseen Academicals

Sam Parry: I am the same age as the Premier League. Same school year. Same interests. My first footballing hero, Brian Deane, scored the competition’s first goal. But friends grow apart. While some of us still kick about in hoodies and trainers, others grow into the starched collar and the meeting room.

The Premier League and this discontent

It was hoodies and trainers for me on February 3rd, 2024. At around 6pm I stood up, shuffled along my row, headed down the gangway and left Bramall Lane. The pub was a short walk away. The bar was rammed. I wasn’t the only one. Sky Sports cameras captured the mass exodus: as microphones picked up the clack of emptying seats, the neutrals not only saw but heard the nakedness of that non-contest. Did they feel short-changed? Thirty minutes in: Sheffield United 0, Aston Villa 4.

2023/24 was a record-breakingly bad season for my football team. It did nothing to bridge the growing schism between the Premier League of my childhood and the one I see now. If that sounds reactionary, perhaps it is – who am I to criticise an institution loved by so many?

Just a fan. A fan of a club queuing to enter the fabled nightclub, with its three-in-three-out system on the door. Eager anticipation as the line gets shorter. This is it. The big time. The promise of a night that every EFL fan is waiting for. But once inside, the hot ticket is displaced by cold realisation: the bouncers have roped off the party and I’m not invited.

The problem, as I have come to see it, is the imbalance between give and take. The Premier League is not unlike a sporting pyramid scheme in which a few clubs within the 92 are nourished to the detriment of the many, and this week we’ve reached the nadir.

The Nadir

It’s Wednesday, September 18th. We’re now two days into the great bottoming-out at the top: Manchester City vs the Premier League. The hearing will not be a win for football, not even if all 115 charges stick. I don’t believe this is ‘the trial of the century’ and the outcome, whether lenient or severe, will not predict real reform. If Manchester City face punishment, it will be little more than a hollow gesture – a spectacle that allows the broken state of the game’s elite to continue unhindered without anything really having to change at all.

Changing the Premier League, really changing it, would require a painful blood-letting. That’s why it doesn’t happen. That’s why the slow handclap of the Manchester City affair suits both parties. Both can justify the time taken as the work of a complex legal matter. Both can preserve the status quo without the dial having to shift. Stretched out and strung along to the tune of ongoing, forthcoming, preceding, months not weeks, a saga, a rumbling on, an appeal – words that dull the sense and heighten the weariness, until bursting the bubble isn’t just assumed to be impossible, but proven so. In the mind’s eye, any real reform blurs on the retina, requiring thinking beyond the hopeful and towards the magical. Christmas voting for turkeys. Sinking ships deserting the rats.

Day three, and this virtue signalling feels cheap. It’s a sleight of hand, leading your eyes one way when they should be glaring down the barrel of something else. But what is that something else? Simple. It’s the competition – or rather, the extent to which competition in the Premier League has been abandoned to big business.

Cultural critic Mark Fisher wrote 15 years ago:

“It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.”

And it’s easier today to imagine the end of the world than Sheffield United beating Manchester City.

The Zenith

Now, I’d like to talk about my club. It’s easier that way. But Sheffield United could be any EFL club – any team securing promotion from the Championship. We could be you. We never expected to get there in 2018/19, in the same way that – I assume – no Ipswich fan would’ve predicted the swiftness of their ascent. But blow me down, there they are. Top flight. Supporters no doubt filled with idling hopes of a top-half finish and the whiff of Europe. I’ve been there, oh yes – still punch-drunk from both the climb and the descent. Not unlike Joni Mitchell’s clouds, I’ve looked at the Premier League from both sides now.

What do I see from the foothills? The fog above. Turbulence and torpor. Upstarts who go down. True, when the top flight beckoned, we came crawling with a splurge of cash for players, wages and redevelopment. And it’s also true that we charged up the table, finishing 9th. But that rise predicted our fall the very next season.

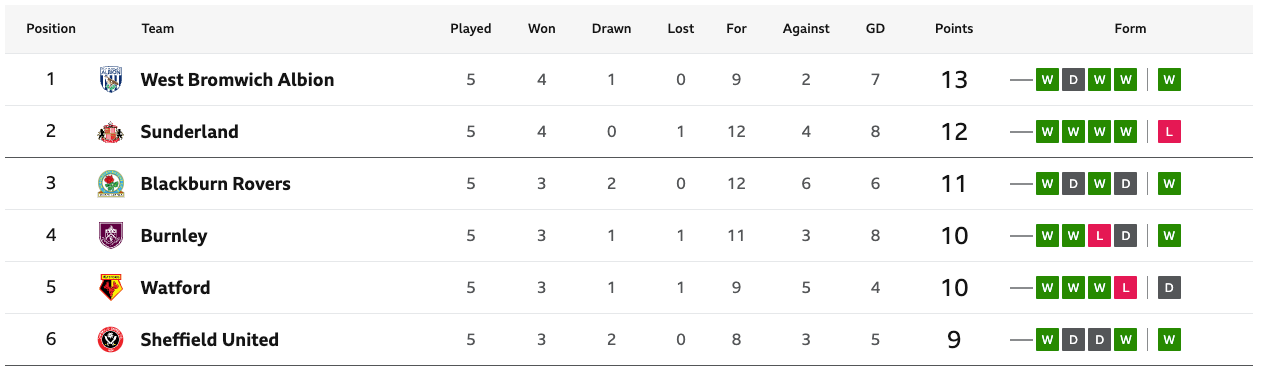

Two years later, we were promoted again. This time, we understood our place. Our suits weren’t stiff enough and our finances were lacking. We intentionally underspent on transfers to stay solvent, which rubber-stamped our relegation from the very first game. It was lucky we were promoted at all, though, because in the Championship we failed to make good on payments to other clubs, leading to a 2-point deduction for 2024/25 – so another season in the second tier might have spelt ruin.

Today, that 2-point deduction masks an auspicious start: three wins and two draws from five games. And here it comes: the nagging, creeping thought getting in where water can’t. We couldn’t, could we?

I’m not counting any chickens because I don’t have a garden, and even if I did, I’m not into fowl of that nature. But every Championship season is a competition. If your team starts well, then the ‘P’ word begins to play on the mind. Promotion, Premier League, pillocked-eight-zip-by-Newcastle. Not another one! We can’t compete.

But we should be able to compete. That is, after all, why we have leagues. The EFL has three of them: the Championship, League One and League Two. That isn’t an arbitrary environment. In horse racing, there are handicaps. In tennis, there is seeding. In football, there are leagues. And leagues exist to create stakes – there should be winners and losers – and provide structure: a natural order of competition.

Teams go up, teams go down. Success is harder to achieve in a higher division than in a lower division, but it is a possibility for all. Likewise, failure is not pre-ordained: season after season, plenty of teams outperform their budget and expectations.

The seams of the Premier League measure up similarly. It is a league. It has 20 teams. They play each other twice. At the end of the season, there is one winner and three are relegated. Somewhere, though, a thread is loose.

The apex always comprises the highest-quality players who are more likely to perform consistently, so it isn’t surprising to see less variation in its title-winners. Still, between 1888 and 1992, just 24 different clubs were crowned English champions – not a gigantic number, so it would be wrong to suggest the top flight was ever a wide-open race.

However, the number has shrunk further. The Premier League has delivered only seven different winners in 32 years, with just four of those winning the title more than once. And, since the turn of the decade, the only team to reach the zenith has been Manchester City – the first English club ever to win four top-flight titles in a row. In the EFL, even accounting for promotion effectively removing a team from that league, it is stark to see such teeming variety within a much shorter time frame:

Championship — 14 different winners (since 2004)

League One — 18 different winners (since 2004)

League Two — 18 different winners (since 2004)

Last season, for the first time since 1997/98, all three newly promoted teams were relegated from the top flight. There’s a real possibility, bordering on a probability, that it could happen again. It seems to me that the natural order of the league system has been deadheaded by the ever-withering yet ever-regenerating hand of the market.

Follow the money

An established pack of around 15 teams enjoy the succour of money flowing into the top flight. So do the other five, plus a handful of yo-yo teams. But it’s the difference between owning a 4-bed house in London and owning a mansion in Kensington with a pool. As prices rise, the rich get disproportionately richer. Even if they didn’t, lurking in the background is a Magwitch, a benefactor, tooled up with lawyers and lump sums.

This only serves to make results and the league table more predictable, year on year. It’s predictability by design, although not through something as shady as conspiracy nor as risible as cock-up. Somewhere in between, an immeasurable number of decisions are made by different actors in various states of natural groupthink. Yes to this. No to that. VAR, lengthy added time and five substitutes instead of three, from a selection of nine instead of seven — changes that suit a particular type of club. The rich ones.

The Premier League is not a start-up. Mature businesses thrive in controlled environments, and the more predictable the outcome, the easier it becomes to plan, manage and contain.

That isn’t to say the top flight is entirely predictable. There are anomalies. I can feel the spittle on my cheek as the apologist scrambles to utter: what about Leicester?

What about Leicester? A solitary surprise winner within a 32-year period that represents 23% of the Football League’s entire history may have surprised the bookies, but their story isn’t at odds with natural variance over more than a century. If Leicester is your answer to the question of proving that the Premier League dream is still alive, then I’m afraid you’re missing nine-tenths of the point.

However, within that 10% there is a valid question. If it’s so bad, why does everyone want to get there?

The Premier League Dream

The top flight remains the dream for most outside it. Players want to play at the highest level. Managers want to manage at the highest level. Owners want to own a Premier League football club. Fans who haven’t tasted it for years will clamour for “ambition”. I did. But running the wrong way down that one-way street is the nascent trend of fans who feel nauseated by the prospect.

The sickness is real, and it’s two-fold: head and heart. The head says that the money involved in the Premier League is now so unsustainable that it risks the financial future of clubs such as Sheffield United, without providing any real balancing effect on the competitiveness of the Premier League itself.

This season, the newly promoted sides – Ipswich, Southampton and Leicester – have collectively spent £278,000,000 on incoming transfers. After the opening four matches, none have registered a win, all have conceded seven or more goals, their aggregate scoreline is 8-22 and #IPSSOT this weekend is already a must-not-lose for both teams. This trio’s great hope? That there are three teams poorer than us. And not just qualitatively poorer on the playing field, but poorer through financial hamstringing, FFP, PSR and points deductions.

Last season, Everton and Nottingham Forest received points deductions during the campaign. As previously stated, my team, Sheffield United, were handed a deduction for this season. Leicester City had a deduction looming over their heads but have avoided the sanction, to the consternation of some. Chelsea and Manchester City are facing charges, as are Everton again, and even Manchester United may be under threat.

However you slice it, the reason for the deductions is money, and the reason for the money is the Premier League. Those financial forces limp down to the Championship in the form of parachute payments, which I worry could soon have the effect of making the Premier League a 26-ish-team league. More than £100 million is available to relegated sides, whilst the rest of the second tier can spend more like £20 million at most. That not only creates financial inequity and impacts the competitiveness of the Championship; it also provides a precariousness cliff-edge for those relegated clubs who aren’t promoted at the first or second time of asking.

As a Sheffield United fan, the heart says “Stop”.

The journey without the destination

Yes, I want to win games of football. I want those games to be challenging, dramatic and competitive. I want – and this may be odd – to lose games and to draw games. I want the playing field to be reasonably level, and if the league is totally imbalanced then I still want the Blades to come out on top. I’m a fan, and winning promotion is blindingly fun. The consequences are not.

It’s a trying sensation, to want the journey but not the destination. And I accept all accusations of fair-weatherism because to feel like this is to desire the good without the bad. All calm, no storm. Yin without the Yang. It’s an insoluble wrangling – like passing your A-Levels with flying colours, only to be returned to the same infantilising classroom of peers, ever-sniping, ever-sneering, always belittling.

Looking back on 2023/24, all I feel now is the brass tacks of it all: the hole in my pocket from money spent on tickets, train fares and grand days out supporting my club amidst the non-contest of the top flight. I have promised myself not to do it again if we get there. Why?

Boredom

The Premier League is so boring. So utterly, chasteningly boring. Boringly predictable. With boring winners and boring tactical uniformity. A commentariat reverting to boring, worn-out descriptions about your “physical, plucky and direct” team. Say nothing of the boring rule changes that have ushered in additional minutes so unwieldy that any underdog win can be overcome, nor the muted celebrations when the goal you’ve scored is inevitably scrutinised by the lethargic bores in Stockley Park.

And that doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of just how boring it is that footballing excellence in this country has rapidly converged around one wealthy dot on the map – away day, anyone, via London again?

Nor does it do justice to the boredom of being an active fan, standing in the away end, cheering on your team despite the inevitability of defeat, only to get nothing back from the home fans because, let’s have it right, when you’re Arsenal and you charge upwards of £1,000 for your cheapest season ticket, you’re far less interested in atmosphere than you are in a target market of high-earners.

Worst of all is the depressing reality that people up and down the country and across the world consume this spectacle – this “product” – as something other than the babyish, boilerplate, airport fiction that the Premier League has come to be.

Looking in the mirror

The thing is, I used to love it. I grew up arm in arm with the Premier League. But he was always going to push me away.

Am I a hipster for hating what once provided me with so much pleasure? Am I a have-not who wishes they had? Am I simply scarred by one bad season? Sure. All of those things. But I’m also just a fan, shaped by the product of my experiences, and for every force pushing me away from the Premier League, I find an equal and opposite reaction in the EFL.

That isn’t to say the Football League is flawless – it isn’t. But to prefer the EFL is to prefer the contest to the non-contest, the unpredictable to the predictable, the various to the homogenous, the drama to the melodrama, the goal to the maybe-goal, and the competition to the procession.

You’ll find integrity in the EFL. You won’t in the top flight, not really, and dressing it up in a sharp suit of imported talents and high finance only hides from supporters the brittle bones beneath. I’ve long been invested in the top of the pyramid, but I’m not signing up again. Because, whether it’s four titles in a row or five, whether Manchester City take the rap for all 115 charges or none, and whether all three promoted sides are relegated or not, nadir and zenith have already collided. I don’t want to linger around the flat-lining of that slowing pulse, all the money in the world, but no friends to share it with.

Great read this Sam, as a little old Wigan fan of over 40 years & seeing my team play 8 years in the money pit league, and i was truly amazed we managed to last that long like many other people was I’m sure! Apart from the first season as i remember & especially the very first game against Chelsea to José Mourinho Chelsea, and getting robbed by a late Crespo strike. The rest was a feeling of, Get us out of this league!! Now I’m very sure The Legend that is Mr Dave Whelan would have scoffed at my thoughts! But it definitely wasn’t for us, and i no now we’ve been through tough times over the years since Mr Whelan sold up. But give me what we have now, a steady well run club anytime. A billionaire owner yes, but a man running us by our means. Hopefully we’ll get the taste of Championship football again sometime soon, but, I’m not interested in tasting the prawn sandwich brigade again thank you. Regards.

Brian Kelsall 👍⚽️

That second to last paragraph is what I have to say to my colleagues and friends who doesn't understand why I don't watch the PL anymore, and haven't for many years. And I too grew up with the PL, and have a lot of good memories, just like you.

And the part about wanting the journey but not the destination really resonates with me. I really want Blackburn to be best and to get promoted, but if they actually do, I know I will end up watching them less.