Why is League Two so old?

Ali Maxwell investigates a phenomenon he discovered by accident...

Ali Maxwell

This wasn’t meant to be an article.

I began writing this as the introduction to the next part of our TRANSFER TARGETS series out next week. It was supposed to spotlight League Two’s hidden gems. Instead, it uncovered something far more striking: beyond the loanees, League Two’s supply of genuine, upward-bound talent is worryingly thin. Why?

League Two got old.

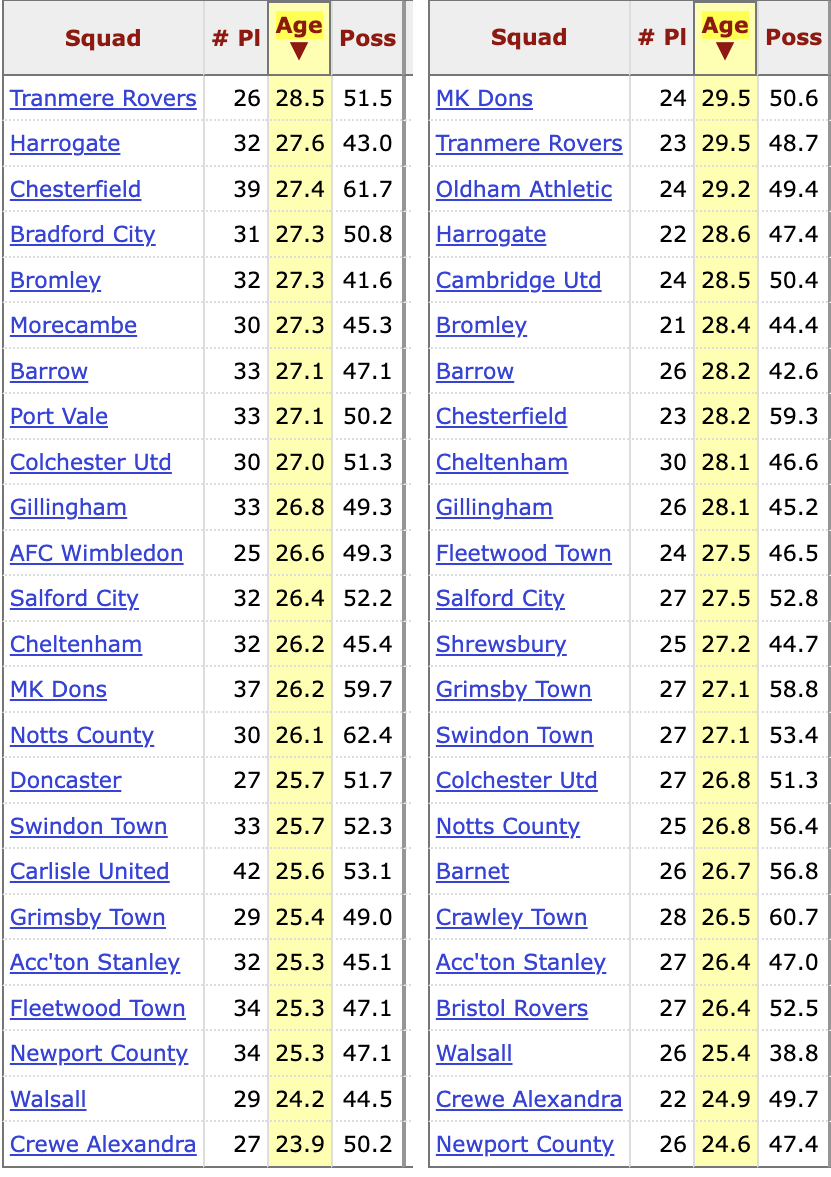

This became clear when I looked at average age data. Here they are, side by side, with 2024/25 on the left and 2025/26 on the right.

The most dramatic squad ageing process happened at MK Dons (+3.3 years per player, on average) and Fleetwood Town (+2.2 years). Tranmere were already the oldest, and got older. A team known as Tranmere Old Boys – Oldham Athletic – joined the league with an average age of 29.2, and Cambridge United came down from League One with an average age that matches last season’s oldest. Colchester and Newport County are the only two teams who have got younger this season.

But the top line is surely this:

Last season, there was one team whose average age was over 28. This season there are ten.

Last season, there were nine clubs whose average age was under 26. This season there are three.

Last season, the average League Two player that took to the pitch was 26.30 years old. This season, it’s up to 27.38 years old, a whole year older per player.

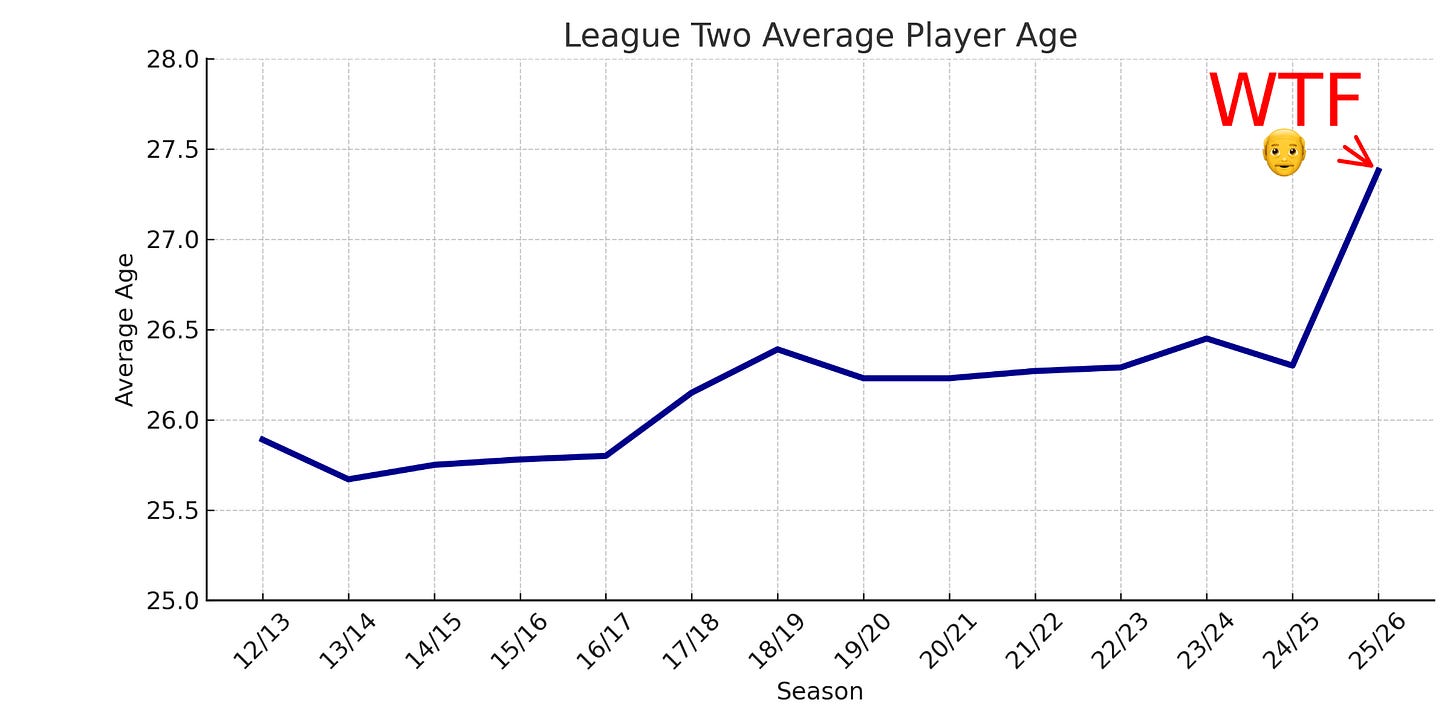

Now, you might think ‘players getting a year older over the course of a year’ sounds like the most natural thing in the world, but it’s not. Here’s the last 14 seasons of the same average age data from the same source.

Since 2012/13, League Two’s average player age hasn’t been lower than 25.67 and it’s never been higher than 26.45 – that’s a total range of 0.78 years across 13 seasons. This summer, however, it jumped 1.08 years in one go.

So, the players are generally older. That means fewer opportunities for young players.

How bad is it?

The total number of club-owned players (no loanees) aged 21 or under who’ve played over half of their team’s minutes this season is only six, and Crewe Alexandra are responsible for four of them: Calum Agius, Owen Lunt, Tom Booth and Lewis Billington. The others are Sam Gale (Gillingham) and Samson Tovide (Colchester United).

NB: Kyreece Lisbie (Colchester) and Lewis Shipley (Barrow) both turned 22 in the last week, which is convenient for my dramatic demonstration of League Two’s lack of opportunity for U21 players.

This isn’t some random quirk – it’s the result of several factors. The following is based on a mix of knowledge, information received, opinion and educated assumptions.

Money – budgets and costs go up up up

Playing budgets in League One have exploded in the past five years, driven by parachute teams and specific cases of extravagant ownership. But it’s not the case that the Big Dogs act in isolation; in fact, they drag the water level upwards with them — the ‘average’ third-tier club has doubled their playing budget in five years.

This is from a Dons Trust piece in the summer that summarised the five previous years of League One and League Two finances:

“The average loss for a League Two club has increased from £0.37m in 19/20 to £2.17m in 23/24. The average loss has got almost six times bigger in five years. The average loss for a League One club in 23/24 was £5.20m, more than three times the 19/20 figure (£1.45m).”

League Two hasn’t exploded to the same extreme as League One, but it has risen across the board. NTT20.COM has knowledge of various League Two clubs that have remained in the division for the last few seasons and whose costs have risen between 25% and 60% without any major change in ownership or general approach. Not only do clubs increase their playing budget to keep up with league rivals, creating a vicious circle, but administrative costs have risen, too. There has been little to no increase in central or Premier League funding in that time period, and the new Sky Sports deal has, per our sources, increased a League Two club’s TV revenue by about 10-20%, from around £1m to £1.1m-1.2m.

Put simply: the average club now spends more money to stand still.

How does that affect young players? Larger playing budgets benefit older players with more experience, such as those dropping down into League Two from higher divisions. These known quantities have more leverage than young players, and they cost more than young players. At this level, higher playing budgets = older players.

The Academy Problem

Running an academy is expensive. Sports science, staffing, safeguarding, infrastructure, analysis – it all adds up. The majority of League Two clubs have Category 3 academies, which can cost anything between £100k and £1m per year.

There are three League Two clubs with Category 2 academies: Crewe Alexandra, Colchester United and Fleetwood Town. These cost an estimated annual £1m-2m to run, which is a serious investment for a club at this level.

Crewe currently have seven bona fide first-team players furnished by the academy and a dozen alumni playing football in EFL divisions or the Scottish Premiership. ColU have only one academy graduate playing regular league minutes for the first team – Samson Tovide – but they’ve recently sold players up the pyramid (Junior Tchamadeu to Stoke, Bradley Ihionvien to Peterborough, Oscar Thorn to Lincoln). Fleetwood have brought Harrison Holgate and Kayden Hughes into the first team, with George Morrison on the fringes; their alumni include Jay Matete (Sunderland), Shayden Morris (Luton Town), Billy Crellin (Glentoran, formerly Everton) and Carl Johnston (Peterborough).

For young players to be brought through, there must be talent and opportunity. There clearly isn’t both right now. Is there neither? Or is there talent but no opportunity?

Seemingly for many clubs, there is a school of thought that the level of compensation received through EPPP (the Elite Player Performance Plan) makes it financially irrational to invest heavily in your academy. If a League Two club develops a gem, a Category 1 club can take him for what often feels like peanuts in the grand scheme of things.

Which leads us to…

The Loan Market: League Two Childcare

This is the perhaps the most under-discussed structural shift. There were 95 loan signings made into League Two this summer – around 4 per club.

Why are there so many loans? Because the pool of players aged 18-21 who are owned by Premier League and Championship clubs is overflowing. Category 1 & 2 academies carry more players per age group than a decade ago, and since post-Brexit rules reduced foreign U18 recruitment, there’s been even more of an arms race around young British talent.

For most in the 18-21 age range, the realistic chance of senior minutes at their club is close to 0%, which has created a huge surplus of young professional players who need to go on loan to play Actual Senior Football.

The ‘best’ ones go straight to the Championship or League One. The others land in League Two. For League Two clubs, this is still hard to resist, because loans are cheap, often subsidised and – in theory – you’re borrowing a player whose talent and exposure to top coaching could see them feasibly be star players in your team, far above the level technically.

I say in theory, because right now in League Two I’d say only a dozen of those 95 loanees would be considered star players for their club – about one in eight. The ‘best-case scenario’ for these loan signings has a low hit rate.

But as a result of there being, on average, four loan players in a League Two squad, club-owned young players have an even bigger battle for fringe minutes. They simply get squeezed out.

League Two now disproportionately develops young players for clubs higher up the pyramid.

Older managers, older players?

League Two managers are older than those in League One or the Championship.

Championship average: 46.5

League One: 45.3

League Two: 49.2

It would be difficult (or at least time-consuming) to prove a hypothesis that older managers = older players. But it doesn’t feel wrong, does it? The exceptions will be just that: exceptions.

Perhaps more pertinently, a League Two manager is operating in a division where sacking rates are high and their job security is fragile. Small margins determine survival, and “winning the battle” – a broad term that covers physical and mental elements of football – is still considered the key driver of success over technical ability, and it’s something to which senior players are more suited.

If results are the key measuring stick for your continued employment, you do not:

Give 700+ minutes to a lightweight academy midfielder

Take time to develop a raw 19-year-old striker

Risk dropping points because a teenager switches off at a set-piece

You absolutely do:

Sign the 29-year-old who has played 250 EFL games

Take three Premier League loans in August

Opt for security over development

Your employers may have told you that ‘developing transfer assets’ was a key part of your remit, but it’s best not to believe any board that pretends they’ll care how player development is going if the team hasn’t won in five games.

Short-termism makes squads older, and English football at this level still hasn’t reached a line in the sand when it comes to managerial lifespan.

The player trading myth

I would describe this as the reversing of a trend.

Thanks to the continued swelling of the transfer market as a larger and larger part of professional football, and in part due to the success – and methods – of Brentford in the Championship, the concept of ‘player trading’ has been all the rage across the Championship, League One and League Two over the past decade.

Broadly, the idea is to buy players, sell them for profit, and continually reinvest in a smart, productive and constant cycle. In doing so, you strengthen both sporting performance and financial sustainability, and your club rises up the footballing food chain in a way that doesn’t come directly from owner funding.

Hand-in-hand with the term ‘player trading’ is the term ‘resale value’. And which players have the greatest ‘resale value’? Young players. So, it’s not a stretch to suggest that, for several years, some League Two recruitment departments have been trying to play the player trading game to some extent.

At this point, there is no evidence of the player trading model working in League Two.

The transfer fees that clubs are able to generate for star players are not big enough to make a significant difference. Per Transfermarkt, in the last four seasons, only Max Dean, Junior Tchamadeu, Ayoub Assal, Ali Al-Hamadi and Joel Randall have fetched over £1m for League Two clubs, while Macaulay Langstaff, Rio Adebisi, Promise Omochere, Connor O’Riordan and Jack Currie were sold for between £500k and £1m.

A sale of £1m – which is about as much as a League Two club can realistically achieve and which happens about once a season, across the whole division – equates to about one-third of the average League Two team’s annual playing budget of £3m. And, in the modern history of League Two, the vast majority of major player sales have come in the form of extraordinary academy talent – Ollie Watkins, Ethan Ampadu, Matt Grimes, Ben Godfrey, Jarrad Branthwaite – rather than clever bits of talent ID and development.

What’s more, the pool of players realistically available to League Two clubs makes the success rate of transfers unreliable. The best released players from Premier League clubs will land higher up the pyramid, or go to a Multi-Club Ownership Group satellite team in Belgium. The best non-league performers will skip League Two and go straight to Peterborough. And barely any League Two clubs have considered foreign recruitment and use of ESC slots to be worthwhile.

When teams do build a good squad and win promotion, they often hit a ceiling around 18th or 19th in League One, at which point their divisional peers’ budgets just get too eye-watering at around £5m. And, with most League Two players on contracts of no longer than two years, any player who performs well in a promotion season is in a position of strength: don’t sign a new contract; prove yourself in League One, playing for a team in which you are comfortable and thriving; and become available on a free transfer after a season at the level, with much greater salary demands, leaving the club needing to build their next successful squad in a higher division and without much or any transfer fee generated. Brutal.

That’s not to say smart transfer business can’t make the team better. And it’s not to say that no League Two clubs have bought, developed and sold players for a profit.

It’s the next stage that hasn’t worked. Phase Two, Phase Three and beyond; reinvestment and further, repeated success, with larger and larger transfer profit going hand in hand with on-pitch success: Forshaw becomes Gray becomes Hogan becomes Jota becomes Maupay becomes Watkins becomes Toney becomes Mbeumo.

I imagine many League Two clubs have asked themselves: what is the actual value to the club of having a young or younger squad? What is the point?

So, those are the reasons I think this has happened. Will League Two ever get its own talent pool back? Will this be the apex, with things starting to revert to normal next season?

The new football regulator is coming in with grand plans to make sure clubs stop ramping up costs. If they succeed, that may lead to clubs getting ‘more creative’ with their spending, getting younger once again.

Also, if Walsall, Colchester or Crewe achieve promotion this year there will likely be some copy-catting — League Two owners will start looking at examples of success and wondering if perhaps cheaper, younger squads look pretty fun after all.

Maybe we should just all embrace getting old!

Excellent read! One comment is that the trend seems to have shifted from being able to sell youth straight from League 2 to the top dogs (I.e. Nick Powell), instead clubs have to sell at a lower price point to clubs in between (Pickering from Crewe to Blackburn) and bank on sell on clauses to reap the rewards down the line if they get another move. Adds a level of chance to the investment and throws off the reinvestment cycle.

Cap doffed. The best article I’ve read all season. This does a very good job of explaining the pressures a League Two manager faces. Lee Bell, as Crewe manager, genuinely has an extra one, in that he is expected to play academy kids alongside whatever on pitch expectations he is handed for the season.